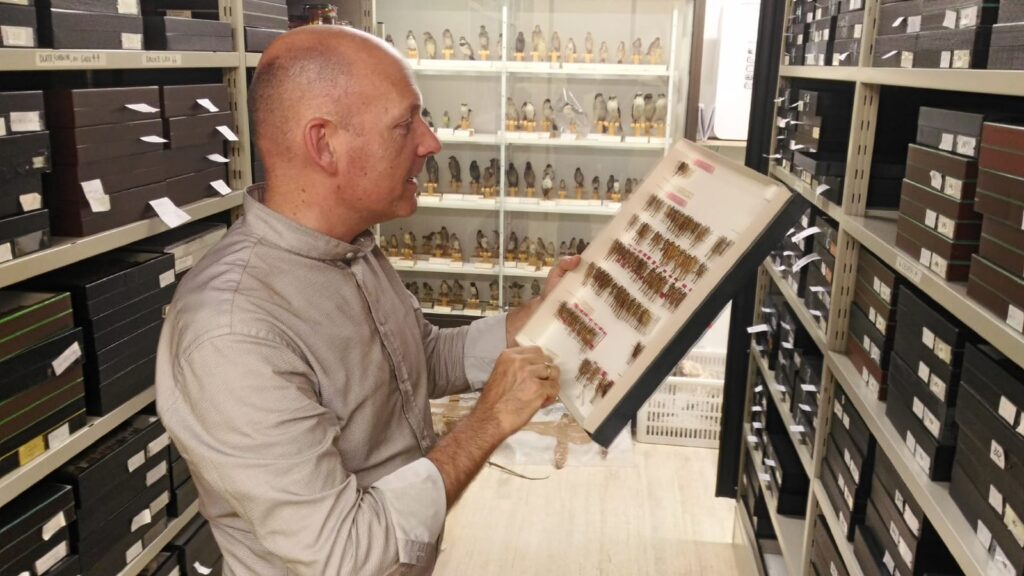

FILIPPO MARIA BUZZETTI

Reading Time: 6 minutes

Oggi facciamo due chiacchiere con Filippo Maria Buzzetti, noto esperto studioso di Ortotteroidei, per conoscerne l’attività in campo bioacustico.

Filippo, ci racconti come hai iniziato?

Bisogna andare moooolto indietro nel tempo, ai tempi dei miei studi universitari e precisamente in Danimarca, dove godevo di una borsa Erasmus presso il Museo Zoologico dell’Università di Copenhagen. Mi occupavo (e mi occupo tuttora) di Gerromorfi, quelle cimici che camminano sull’acqua. La feci le prime raccolte di campo e decisi di svolgere la tesi in entomologia. Al rientro in Italia cominciai a frequentare l’AENV (Associazione Entomologica Naturalistica Vicentina, allora l’associazionismo era molto più vivo di adesso in cui tutti riusciamo a incontrarci sui social) dove incontrai Paolo Fontana, allora tecnico di laboratorio presso il dipartimento di Entomologia della facoltà di Agraria a Padova: lui è stato il primo entomologo ad ascoltare senza supponenza i miei dubbi e le mie richieste da neofita. Volevo svolgere la tesi sui Monti Lessini, con argomento i Gerromorfi, ma Paolo mi convinse a concentrarmi sugli insetti Ortotteroidei (cavallette, grilli, mantidi e insetti affini). Fu così che cominciai a raccogliere sistematicamente questo gruppo di insetti e mi trovai presto a che fare con l’identificazione del genere Glyptobothrus, la cui determinazione delle specie è sicura solo su base bioacustica, analizzando il canto del maschio. I miei genitori mi regalarono un registratore DAT che campionava fino a 48000Hz, con questo feci le mie prime registrazioni… pessime! Dovetti esercitarmi molto e ricordo con quanta fatica mi destreggiavo fra cavi, libretto per le annotazioni, microfono, prolunga (l’antenna di una vecchia radio che ancora uso!), macchina fotografica, zaino, retino entomologico…

E più di recente?

Finalmente le registrazioni in campo e in laboratorio non costituiscono più un problema ma sono diventate delle piacevoli scoperte, anche se si tratta di analizzare il canto di una specie nota: raggiungere l’identificazione grazie al confronto delle mie registrazioni con le analisi pubblicate costituisce per me un vero piacere intellettuale. Forse anche perché non riesco a dedicarci tutto il tempo che vorrei. Inoltre ho avuto la fortuna di incontrare Cesare Brizio che mi ha spinto ad approfondire il livello e la qualità delle analisi.

Che attrezzature usi?

Mi trovo bene con Ultramic della Dodotronic (sarò sempre debitore a Ivano Pelicella per aver ideato quello strumento perfetto per le mie esigenze!), registro con un telefonino Samsung e l’app Bat Recorder. Salvo le registrazioni come file in una cartella Drive. Quanto è cambiato dagli inizi!

C’è qualche specie o gruppo di specie che ti ha preso particolarmente?

La soddisfazione più grande degli ultimi anni è stato registrare il canto del maschio di Uromenus annae, una specie di Ensifero endemico di Sardegna che si pensava estinto. Come se una voce dicesse: “Ci sono ancora!”.

Progetti futuri?

Sopprimere degli esseri viventi per scopo di studio impone dei problemi etici che devono essere tenuti in conto se non si vuole essere superficiali. Per questo la bioacustica è un formidabile strumento per lo studio non invasivo della biodiversità, che può contribuire efficacemente ad avvicinare un pubblico più ampio allo studio e alla tutela della Natura. Svolgere azioni di conservazione senza sopprime l’oggetto (parola freddissima e terribile qui!) è una conquista a cui solo recentemente molti studiosi, soprattutto entomologi, hanno accettato di avvicinarsi. . Collaboro come entomologo con la Fondazione Museo Civico di Rovereto che è capofila di due progetti di conservazione che hanno come strumento base il monitoraggio bioacustico.

Il primo riguarda Uromenus annae, in collaborazione con Laura Loru del CNR IRET di Sassari, Roberto A. Pantaleoni della sezione di Entomologia del Dipartimento di Agraria dell’Università di Sassari e associato CNR IRET e M. A. Francesca Fiori di Nuoro che, con il supporto di Manuela Manca, Giovanni Bassu e Nicola Sanna dell’Agenzia Regionale F.o.Re.S.T.A.S. (Servizio Territoriale di Nuoro).

Il secondo progetto ha come obiettivo lo studio e conservazione di Zeuneriana marmorata, un Ortottero ensifero endemico della costa Nord Adriatica, oggi presente con poche popolazioni relitte, in collaborazione con Axel Hochkirch (Università di Trier), The Mohamed bin Zayed Species Conservation Fund e i colleghi naturalisti Francesca Tami, Yannick Fanin e Pierpaolo Merluzzi.

English version

Today we have a chat with Filippo Maria Buzzetti, a well-known expert in Orthopteraids, to learn about his activity in the bioacoustic field.

Filippo, can you tell us how you started?

We have to go back in time loooong, to the days of my university studies and precisely to Denmark, where I enjoyed an Erasmus grant at the Zoological Museum of the University of Copenhagen. I took care (and still do) of Gerromorphs, those bugs that walk on water. I made my first field collections and decided to do my thesis in entomology. Upon returning to Italy, I began to attend AENV (Vicentine Naturalistic Entomological Association, then associations were much more alive than now where we can all meet on social networks) where I met Paolo Fontana, then a laboratory technician at the Entomology department of Faculty of Agriculture in Padua: he was the first entomologist to listen without arrogance to my doubts and requests as a neophyte. I wanted to carry out the thesis on the Lessini Mountains, with the Gerromorphs topic, but Paolo convinced me to focus on Orthoptera insects (grasshoppers, crickets, mantises and related insects). Thus it was that I began to systematically collect this group of insects and I soon found myself dealing with the identification of the genus Glyptobothrus, whose species determination is safe only on a bioacoustic basis, by analyzing the song of the male. My parents gave me a DAT recorder that sampled up to 48000Hz, with this I made my first recordings… bad! I had to practice a lot and I remember how hard I was juggling cables, note book, microphone, extension cable (the antenna of an old radio that I still use!), Camera, backpack, entomological net…

And more recently?

Finally, the recordings in the field and in the laboratory are no longer a problem but have become pleasant discoveries, even if it involves analyzing the song of a known species: achieving identification thanks to the comparison of my recordings with the published analyzes is for me a real intellectual pleasure. Maybe also because I can’t give it as much time as I would like. I was also lucky enough to meet Cesare Brizio who pushed me to deepen the level and quality of the analyzes.

What equipment do you use?

I am happy with Ultramic from Dodotronic (I will always be indebted to Ivano Pelicella for having created the perfect tool for my needs!), I register with a Samsung mobile phone and the Bat Recorder app. I save the recordings as files in a Drive folder. How much has changed since the beginning!

Is there any species or group of species that has particularly gripped you?

The greatest satisfaction in recent years has been to record the singing of the male of Uromenus annae, a species of endemic Ensifer of Sardinia that was thought to be extinct. As if a voice were saying: “I’m still there!”.

Future projects?

The suppression of living beings for the purpose of study imposes ethical problems that must be taken into account if one does not want to be superficial. For this reason bioacoustics is a formidable tool for the non-invasive study of biodiversity, which can effectively contribute to bringing a wider public closer to the study and protection of Nature. Carrying out conservation actions without suppressing the object (very cold and terrible word here!) is an achievement that many researchers, especially entomologists, have only recently agreed to approach. I collaborate as an entomologist with the Fondazione Museo Civico di Rovereto which is the leader of two conservation projects that have bioacoustic monitoring as a basic tool.

The first concerns Uromenus annae, in collaboration with Laura Loru of the CNR IRET of Sassari, Roberto A. Pantaleoni of the Entomology section of the Dipartimento di Agraria dell’Università di Sassari and associate CNR IRET and M. A. Francesca Fiori di Nuoro who, with the support of Manuela Manca, Giovanni Bassu and Nicola Sanna of the Agenzia Regionale F.o.Re.S.T.A.S. (Servizio Territoriale di Nuoro).

The second project aims at the study and conservation of Zeuneriana marmorata, an endemic orthopteran endemic of the North Adriatic coast, present today with few relict populations, in collaboration with Axel Hochkirch (University of Trier), The Mohamed bin Zayed Species Conservation Fund and colleagues naturalists Francesca Tami, Yannick Fanin and Pierpaolo Merluzzi.

Commenti recenti