VICKI POWYS

Reading Time: 6 minutes

Vicki Powys, 73 yo, from Australia, has been recording wildlife since 1986. She has authored many papers and articles on birdsong, and for 12 years was sound editor for the Australian Wildlife Sound Recording Group. Vicki is a landscape artist who has travelled widely within Australia, taking her paints and canvases plus various recording devices to capture some natural ambience. Her recordings are lodged with the British Library, the CSIRO (Australia) and Cornell (USA) archives. Vicki uses recording as an investigative tool to gain a closer understanding of nature, and for the joy of remembering wonderful places visited. Vicki’s website www.caperteebirder.com outlines many accessible DIY recording methods, useful to both beginners and experienced recordists.

Today we have a chat with her to know more about her activity in the bioacoustic field.

Vicki, can you tell us how you started?

I started recording using very basic equipment, simply as a means to learn birdsong. My interest in birds began in 1970. I had moved from city to country armed with a bird book and a vinyl record “The Birds Around Us” with calls of 33 common Australian birds. Then when the Atlas of Australian Birds mapping project began in 1977, the ability to identify birds by their calls became an essential skill for us ‘citizen scientists’.

What recording equipment did you first use?

In the late 1970s birdsong identification tapes became available. I too wanted to record birds, but could not afford the heavy reel to reel tape recorders that professionals used. It was not until 1986 that, on a painting and bushwalking trip to Central Australia, I carried in my pocket a tiny Aiwa microcassette recorder and obtained my earliest birdsong recordings. The quality was poor but replaying those tapes does bring back memories!

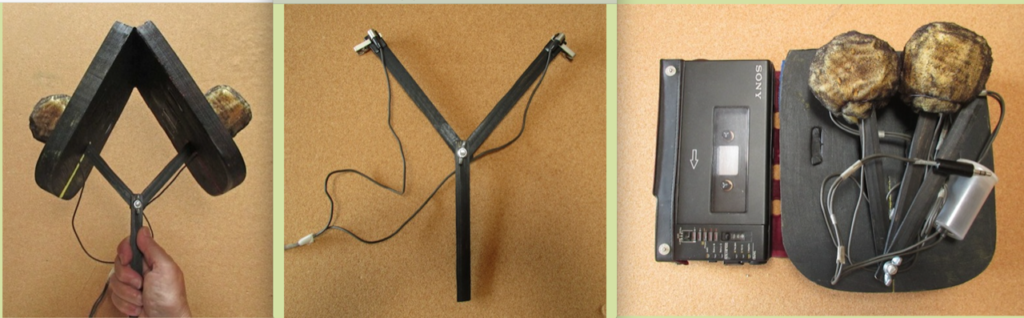

Also with the microcassette recorder, I documented the regional dialects of my local lyrebirds in the Central Tablelands of New South Wales. The tape quality was just adequate for my purposes, and good enough for scientist Ederic Slater to make sonograms for me on a Kay Sonograph Machine at CSIRO in Canberra. Bird songs as patterns – what a wonderful concept! (In those days there were no home computers and no audio software!) I attended one of Ed Slater’s first workshops in 1990, and also joined the Wildlife Sound Recording Society in the UK and became a founding member of our own Australian Wildlife Sound Recording Group. In 1990 I upgraded to a Sony Walkman cassette recorder WMD6C, and being keen to record stereo soundscapes, I added two omni lavalier mics with a home-made folding closed-cell foam baffle for some quite good stereo sounds. I used this setup on another outback trip, with some success. By now the British Library had contacted me requesting some Australian wildlife sounds for their natural history section, and I was more than happy to oblige.

I upgraded again in 1993 to the much heavier Sony TCD-D10 Pro DAT recorder which I used with a Sony ECM-MS5 one-point stereo mic. I took the DAT on a trip to Kakadu National Park where at a crocodile-filled waterhole I carefully laid out 70 metres of stereo cable to a mic placed at the water’s edge, leading back to my tent which I hoped was a safe distance from those crocodiles. I could listen in at night to the eerie splashes and shrieks of the billabong, it really was quite scary!

What equipment do you use now?

By the late 1990s home computers and audio software became available – it was a steep learning curve for us all! But at last we could make our own sonograms and study the science of birdsong and other natural sounds. Now everybody could be a bioacoustics scientist!

In 2002 I became sound editor for the Australian Wildlife Sound Recording Group and I had to quickly learn how to integrate old and new technologies. Members’ contributions would arrive via Australia Post in various older formats and I needed to digitize them to create an audio CD for our members. There were minidiscs, analogue and digital cassettes, reel-to-reel tapes, digital files on CDs, plus a few very short audio mp3 files via email. At that time I had dial-up internet and an aqua-coloured iMac with add-on CD burner that often failed for no good reason.

Before too long, maybe 2008, new recorders were using Compact Flash and SD cards, so that digitally recorded sounds could be transferred direct to our computers – no analogue stage was needed! I bought a Sound Devices 702 recorder, an Olympus LS10, some decent microphones and a Crown SASS binaural-like head. I also tried silicone ears and yoga-block baffles with a variety of mics from cheap to expensive. The Crown SASS with pro mics gave good sound but was rather heavy and cumbersome for field work. I made another SASS from a closed-cell foam yoga block, adding Primo 172 electret mics. It was so much lighter for field work, it worked well and has been my go-to array for some years now. With encouragement from Rob Danielson of the Boundary Mics group, I tested my lightweight DIY rigs against professional equipment and many of these tests and mic comparisons are shown on my website. It was interesting that the cheap electret mics were actually more reliable than the expensive mics which, despite manufacturers’ claims, often hissed and spluttered at crucial moments.

I have two favourite set-ups – firstly with two Sennheiser 8020 mics in a home-made yoga-block SASS arrangement, running to the SD702. This gives excellent results and can also record at high resolutions (192k) for sounds of microbats and ultrasonic insects. For the bats, I also have a hand-held bat detector for a preliminary survey, to know if a recording is worthwhile.

Secondly, and most often used, is the little Olympus LS10, connected either to a Sennheiser ME66 gun mic, or to the home-made SASS which uses two pairs of Primo EM172 electrets. In the summer months I keep this latter rig on my front verandah with a 3-metre cable running to the LS10 on my bedside table, so I can listen at night to munching wallabies, the crazy calls of nightjars and squabblings of possums!

Is there any species or group of species that has particularly gripped you?

I am an opportunistic recordist, for me recording is a tool with which to investigate nature, for example using hydrophones to listen to underwater sounds, or a gun mic to document the individual repertoires of birds, insects and other animals. So I tend to record first, then ask questions later. I have been interested in Superb Lyrebirds for many years. I also love frog sounds, and I have discovered two undescribed species of crickets having first noticed them by their calls. I wrote up a study on the buzz-pollination sounds of my local native bees. Anything in nature that makes a sound, interests me!

What do you think about soundscapes?

Soundscapes are wonderful, they give a sense of ‘being there’ and bring back memories of places, as well as having great historic and scientific value. Hopefully, more people will be encouraged to listen closely to our natural soundscapes and move to protect them from ever-increasing anthropogenic noise.

Future projects?

I need to bring my wildlife sound archive up to date! Maybe I will go on another recording trip somewhere. I’ve recently started making videos of my local birds for YouTube https://m.youtube.com/channel/UCQ_N9kWupJDKduifQKwRiWQ. There’s plenty more articles I could write. And those MixPre 3s are looking good!

13 January 2021

Commenti recenti